Preserving and Empowering LGBTQ+ Lives With Maps

Travel

We often think of maps as tools that help us get from A to B. While that might be one of their most useful functions, maps can be so much more than that — especially for communities that have historically been marginalized and underrepresented. A story by Snigdha Bansal at TomTom

For LGBTIA+ people, location data and maps are often less about taking them where they want to go and more about telling them where they can go. Apart from pointing out safe spaces and those they must avoid, maps also serve as proofs of the existence of the queer community — especially in a world that repeatedly tries to erase and overwrite their history.

For LGBTIA+ people, location data and maps are often less about taking them where they want to go and more about telling them where they can go. Apart from pointing out safe spaces and those they must avoid, maps also serve as proofs of the existence of the queer community — especially in a world that repeatedly tries to erase and overwrite their history.

Maps targeted towards queer people have been around for a long time. There have been many attempts to chronicle queer lives and history using cartography. One such initiative is the Damron Address Books — a travel guide for gay men first published in the 1960s and in circulation as recently as 2020.

Created by Bob Damron, a gay businessman keeping track of his experiences travelling around the US, the guides came to resemble the historic 'Green Book' that helped Black travellers find safe spaces from 1936 to 1967. From 1964 to 1980, Damron helped queer people across the US find safe spots.

Immortalizing queer history on maps

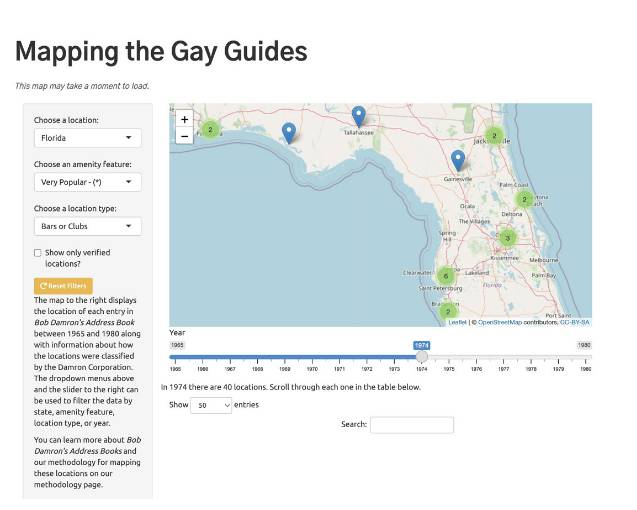

In today’s digital world, interest in physical guidebooks is waning, as is the need for an easy-to-hide pocketbook in an America where it’s no longer illegal to be gay. Now, Damron’s guides are being digitized in the form of a searchable map by Eric Gonzaba, assistant professor of American studies at CSU Fullerton, and Amanda Regan, assistant professor of History at Clemson University. Mapping the Gay Guides visualizes “the growth of queer spaces between 1965 and 1980” by associating geographical coordinates with each location mentioned in the Damron Address Books.

Through a searchable digital map, Mapping the Gay Guides provides a glimpse into the lives and growth of queer communities in the USA between 1965 and 1980. Credit: Mapping the Gay Guides.

As people begin to find communities online, the immediate need for physical guides might have diminished, but they can now serve as vignettes of the lives of queer people in the US before the Internet.

“Currently, our site has over 34,000 locations spanning from 1965, which is noteworthy because that's before the Stonewall riots which are typically noted as a moment that changed LGBTQ+ history,” Regan tells me.

“The fact that these guides existed before (Stonewall) points to the fact that there was a visibly large LGBTQ+ community around the country — not just in the metros of San Francisco and New York.”

Not only does this resource serve as proof of existence, but it also helps people understand where queer communities were located, how they grew, and how they lived and moved over time. One can explore the maps, filtering by location and time period to see how the community was affected by pivotal historical events like the AIDS crisis, for instance.

Representing this information on maps gives these communities a sense of belonging to the places they’ve been to, places they thought they were alone in and places that mean something to others like them. The Mapping the Gay Guides team constantly receives e-mails from people who have connections to the places on their map.

“They often say, ‘I went to that bar in the 70s and seeing it on the map brought back so many memories. Thank you for putting our history on there.’”

Similar maps have been made to immortalize queer history in other parts of the world. Pride of Place attempts to uncover and celebrate places of LGBTQ+ heritage across England, spanning from Roman Britain to contemporary landmarks. It was created by the Cultures of the Body, Gender and Sexuality research group at Leeds Beckett University.

Similar to the Mapping the Gay Guides map, this map depicts locations and landscapes of importance to England’s LGBTQ+ history — from buildings commemorating figures like social reformer Eleanor Rathbone to locations of important events such as the site of Sheffield's first Pride event in 2008. By showing places and events from 1096 onwards, it underlines that queer history exists all around us.

“A map is a piece of historical data that is really vital for us to record ourselves in and to exist in because we've been here forever, we're going to be here forever, but our histories aren't recorded that well, or they're often destroyed or misremembered,” says Oscar N Fitzpatrick, activist and consultant for activism.

As places of importance disappear, these historical maps also serve as reminders that a place that might look like any other building today holds an important place in LGBTQ+ history.

Mapping modern lives and experiences

Maps can also help queer people identify safe spaces and find community. Everywhere is Queer is a website that contains a map of queer-owned businesses worldwide. It was conceptualized and created by Charlie Sprinkman, who used to travel around the USA working with an organic beverage company. During these trips, he’d have to look up “queer hangouts” in every place he visited, which sparked the idea of creating a modern version of the Damron Address Book.

Since its launch in January 2022, the map has listed hundreds of businesses, mostly in the US but also in Germany, Spain, South Africa, the UK, Costa Rica and Mexico. In just months, it has helped people connect with each other, as well as promoting queer-owned businesses. When in a new place, digital maps are a useful resource for queer people to find safe spaces.

These maps are especially important when people find themselves in a new space, says Fitzpatrick. “Take a displaced person or a refugee who arrives in a new city. Knowing where the queer people are, where their community is and finding an accessible route to them is really useful for them.”

Maps are also being used to tell queer stories which are rooted in location. People often attach importance to places they had memorable experiences at. But when these experiences can’t necessarily be talked about openly, mapmaking can be a covert way of sharing those stories with the world.

Queering the Map is a crowdsourced map of queer experiences around the world. Queer people across the globe can anonymously add their own experiences to geographical spots where they happened, be it moments of self-discovery or coming out stories.

The stories maps don’t tell

These maps act as powerful resources in many ways, but they might not always show the complete picture.

Mapping the Gay Guides, for example, shows the world from Damron’s perspective — a white gay man in 20th-century America. Consequently, the locations are tailored to white gay men, and the perspective of women, trans people and people of colour is not represented by his guides. In fact, Damron categorizes some places in a way that ‘cautions’ the reader about the presence of African American people or drag performers.

In their digitizing process, Gonzaba, Regan and other contributors keep these details consistent. Regan advises people to ‘read against the grain’ and not consider this map the Holy Grail of queer life in those decades.

“I often show my student's historical maps in my class and implore them to investigate the biases of the maps and their authors. I think a good map is one that you can be critical of,” says Regan. This map will soon be 116,000 location listings stronger, thanks to a National Endowment for the Humanities grant that makes it possible to map Damron’s entries from 1981 to 2005.

On their website, the creators of Pride of Place also mention how their maps, and LGBTQ+ past in general, have abundant information about gay men — whose histories and voices were considered more worthy of focus than “lesbian, bisexual, trans, working-class, disabled, Black and ethnically diverse voices.” Since this information is crowdsourced, they welcome entries about these underrepresented communities whose stories are equally rich and powerful.

Using maps to inspire change

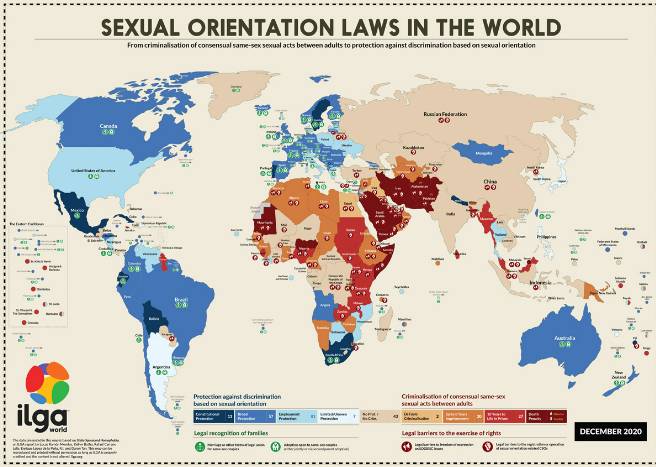

These mapping initiatives are rooted largely in the past, which is what most maps represent. But when we cast our eyes toward the future, they can also be used to bring about much-needed change for vulnerable communities. Fitzpatrick, who also works with the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA), uses maps in his advocacy to impress the need for action upon policymakers.

ILGA releases a yearly map visualizing where it’s safe to be queer in the world from a legal and social perspective. Credit: ILGA World, 2020.

He says, “We don’t always want to show people violent imagery to make them understand how much we need policies that support us. For people who don’t know what violence against LGBTQ+ people looks like, a map is an amazing visual reference.”